Jorge Lanata

Jorge Lanata | |

|---|---|

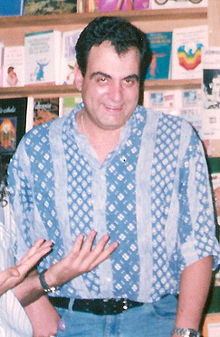

Lanata in 2019 | |

| Born | 12 September 1960 Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina |

| Died | 30 December 2024 (aged 64) Campanario Jardín de Paz cemetery, in Florencio Varela, Argentina |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1974–2024 |

| Known for | Reporting on the K-Money political scandal |

| Spouses | Patricia Orlando

(m. 1984; div. 1986)Sara Stewart Brown

(m. 1998; div. 2016)Elba Marcovecchio (m. 2022) |

| Partner | Andrea Rodríguez (1986–1989) |

| Children | 2 |

Jorge Ernesto Lanata (12 September 1960 – 30 December 2024) was an Argentine journalist and author. He founded the newspaper Página 12 in 1987,[1] and worked on several TV programs, newspapers, magazines and documentaries. He moved to the Clarín Group in 2012, and hosted Lanata sin filtro on Radio Mitre and Periodismo para todos on El Trece. He won several awards, including the Golden Martín Fierro Award. He was hospitalized in 2024 with several health problems, and after some months he died on 30 December 2024.

Biography

[edit]

Lanata was born in Mar del Plata. His grandfather was Agustín Lanata, a well known footballer of the early 20th century.[2] He lived his first years at Sarandí, Buenos Aires. He started working at an early age, as a waiter and technician at Radio Nacional. He wrote an essay about the cinema of Argentina, which earned a municipal award.[3]

He started his career in journalism in 1977, in the magazines Siete Días and El Porteño. He founded the newspaper Página 12 in 1987, aged 26.[3] The newspaper outed a request for bribes from the government of Carlos Menem to the Swift company, starting the Swiftgate scandal.[4] Following a cocaine trafficking investigation started in Spain, the newspaper started the Yomagate scandal as well.[4] In 1990 he founded the magazine Página 30, and in 1998 the magazine Veintiuno.[3] He also hosted two radio programs, Hora 25 and Rompecabezas.[3] He also founded the newspaper Crítica de la Argentina in 2008, but it fell into bankruptcy a pair of months later.[3] Working at the Perfil newspaper he reported the discovery by the police of a bag of money in the private bathroom of the minister Felisa Miceli. She was sentenced to prison in 2012 because of this.[4]

Lanata also worked on documentaries. He filmed Deuda, a film about the external debt of Argentina, and Tan lejos, tan cerca: Malvinas, 25 años después, a film about the Falkland Islands on the 25th anniversary of the Falklands War.[3]

Día D and Detrás de las Noticias, his first TV program, started in 1997, both on América TV.[3] He returned to television with the TV program Después de Todo, aired by Canal 26 from 2009 to 2011. He moved to the Clarín Group in 2012, and wrote editorial pieces for the Clarín newspaper. He hosted the radio program Lanata sin filtro on Radio Mitre; the testimony of Laura Muñoz in the program started the Ciccone case that investigated if vicepresident Amado Boudou had used strawmen to save the printing house Ciccone Calcográfica from bankruptcy.[4]

He started the TV program Periodismo para todos.[3] One of the investigations of the program, the K money trail, revealed a scheme of money laundering that led to the sentencing of Lázaro and Martín Báez.[4] The program won several awards, and during the 2013 edition of the Martín Fierro Awards he coined the term "la grieta" ("the chasm") to describe the political polarization in Argentina, a term that became mainstream since then.[3] He started the unsuccessful TV program El argentino más inteligente in 2015, and won the Golden Martín Fierro Award on that year.[3] Because of his ongoing health problems Periodismo para todos had no 2019 season, and he reduced his participation in Lanata sin Filtro to that of a columnist. The program returned in 2020, and had its last season in 2023.[3]

Books

[edit]

Jorge Lanata is also the author of several fiction and non-fiction books. His first work was a collaboration for the 1987 book El nuevo periodismo, written by several new journalists of the time. The next year he wrote La guerra de las piedras, based on his work as a correspondent of Página/12 during the First Intifada. Polaroids narrated events featuring diverse public people, such as writer Tomás Eloy Martínez, singer Fito Páez and military Emilio Massera. Historia de Teller, written in 1992, was his first work of fiction, the story of a rock star who, tired of the fame, retires to a secluded life in Venice. Cortinas de Humo is an investigative book based on the two terrorist attacks against the Jews in Argentina, the 1992 Buenos Aires Israeli embassy bombing and the AMIA bombing. Vuelta de página is a collection of his investigations and editorial pieces written for Página/12, published by the time he left the newspaper.[5]

His first successful book was the 2003 Argentinos, which was focused on the history of Argentina from colonization to the modern day. It was delivered in two parts, with the Argentina Centennial at the end of the first book. Lanata mentioned that he wrote it during the December 2001 riots in Argentina. It sold over 500,000 books, and was reissued in 2008 as a single book. In a similar style, he published ADN. El mapa genético de los defectos argentinos in 2004. Enciclopedia universal del verso is a collection of articles written for the magazine XXI. In 2007 he wrote a new novel, Muertos de amor, a historical novel set in the Dirty War, about a guerrilla fighting in the north of Argentina. Hora 25, from 2008, and 26 personas para salvar al mundo, from 2012, are collections of interviews.[5]

The 2014 book 10K, la década robada focused on the corruption scandals that took place during the presidencies of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the conflict between Kirchnerism and the media. He wrote an autobiography in 2017, 56. Cuarenta años de periodismo y algo de vida personal. In 2023 he wrote the best-seller Óxido. Historia de la corrupción en Argentina, about corruption scandals across the history of Argentina, with was at the top of the most sold books list for nine weeks.[5]

Personal life

[edit]Angélica, the foster mother of Jorge Lanata, was bedridden and unable to talk during most of his infancy. As a result, he was raised by his aunts. His first long-term partner was Patricia Orlando, whom he met in 1984 on his radio program "Sin Anestesia". He left her two years later for Andrea Rodríguez, whom he also knew from his radio work. Lanata and Rodríguez had their first daughter, Bárbara, in 1989. He left Rodríguez that same year, although he had a cordial relationship with his daughter. He married the journalist Silvina Chediek in 1990 in New York and got divorced a year later. The reasons for this were never disclosed.[6]

After some years being single, Lanata met Sara Stewart Brown on the studios of the Día D program. They married in secret in 2011 and had a daughter, Lola, the second daughter for Lanata. Brown donated a kidney in 2015 to a child and the child's mother did the same for Lanata, saving his life. They divorced in 2016, as Brown and Lanata had conflicts over Lanata's busy lifestyle.[6]

Elba Marcovecchio was his last wife. Unlike his previous relationships, Lanata had no problem talking about their romance in celebrity magazines. They were married by the priest Guillermo Marcó, who used to be the spokesman for Jorge Bergoglio, later known as Pope Francis. They lived in individual apartments in the same building, and Lanata developed a close relationship with Marcovecchio's two kids. When Lanata was hospitalized, Marcovecchio had public disputes with Lanata's daughters, who accused her of abusing his credit cards and stealing from his private office. They also had disagreements over who could take decisions about his health while he was in a coma. Those conflicts ended in mediation with judge Lucila Inés Córdoba.[6]

Health problems and death

[edit]

Jorge Lanata suffered from several health problems. His medic Julio Bruetman explained them in the biography Lanata. As he had deep sleep apneas he required breathing devices during the night. He also had a kidney failure, being hospitalized several times, and had to undergo kidney dialysis. He also had type 2 diabetes as a result of his overweight. In 1999 he had a weight near 150 kilograms, and got near to a diabetic coma. He was also a frequent smoker and never left the habit despite medic orders, even smoking on live television. He also consumed 8 grams of cocaine during a decade, until he underwent a detox treatment in the United States.[7]

Jorge Lanata entered the Hospital Italiano in June 2024. He was transferred to the Santa Catalina clinic on 11 September for neurological rehabilitation, but had to be returned less than a month later for kidney problems. He underwent surgery for intestinal ischemia on 9 October, which removed 70 centimeters of intestines. His health never got stable enough to be moved to the clinic, as his family desired. Marcovecchio told the press that in his last weeks he was serene and accepting of his upcoming death, and that there was nothing else the doctors could do about it.[8] He died on 30 December 2024, as a result of multiple organ failure.[9]

The funeral was held at the House of Culture of Buenos Aires, on 1 and 2 January. It was open to the public, and was attended by his family, Chano Moreno Charpentier (the singer of Tan Biónica), journalists Ernesto Tenembaum, María O’Donnell, Eduardo Feinmann, Nicolás Wiñazki, Nancy Pazos, Mercedes Ninci, Fernando Bravo, Joaquín Morales Solá, Nacho Otero, Diego Leuco, and Luis Majul, and producer Pablo Codevilla. Politician Patricia Bullrich sent a funeral wreath. Afterwards, he was buried at the Campanario Jardín de Paz cemetery, in Florencio Varela.[10]

Several politicians sent their condolences after his death, such as Elisa Carrió, Carolina Píparo, Ramiro Marra, Fernando Iglesias, Patricia Bullrich, Maximiliano Ferraro, Marcela Pagano, Jorge Macri, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, Luis Petri and former president Mauricio Macri. The Radical Civic Union sent a message with its institutional X account.[11] President Javier Milei made no public comments about his death at the moment, fearing that any comment from him would be turned into a political dispute.[12]

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award | Year | Work | Category | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martín Fierro Awards | 1996 | Rompecabezas | Best radio journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 1996 | Día D | Best TV journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 1996 | Personal | Best work in journalism | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 1997 | Día D | Best TV journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 1997 | Personal | Best work in journalism | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 1999 | Día D | Best TV journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 1999 | Personal | Best male work in journalism | Nominated | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2001 | Personal | Best male work in journalism | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2003 | Personal | Best male work in journalism | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2005 | Personal | Best male work in journalism on radio | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2012 | Personal | Best male work in journalism on radio | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2012 | Periodismo para todos | Best TV journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2013 | Personal | Best male work in journalism | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2013 | Periodismo para todos | Best TV journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2014 | Personal | Best male work in journalism on radio | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2014 | Periodismo para todos | Best TV journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2015 | Personal | Best male work in journalism | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2015 | Periodismo para todos | Best TV journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Martín Fierro Awards | 2015 | Personal | Golden Martín Fierro award | Won | [13] |

| Tato Awards | 2012 | Periodismo para todos | Best journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Tato Awards | 2012 | Personal | Best male work in journalism | Won | [13] |

| Tato Awards | 2013 | Periodismo para todos | Best journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Tato Awards | 2013 | Personal | Best journalist host | Won | [13] |

| Tato Awards | 2013 | Periodismo para todos | Program of the year | Won | [13] |

| Tato Awards | 2015 | Periodismo para todos | Best journalist program | Won | [13] |

| Tato Awards | 2015 | Personal | Best journalist host | Won | [13] |

| Konex Award | 1997 | Personal | Diploma of Merit – Journalistic Direction | Won | [13] |

| Konex Award | 2007 | Personal | Diploma of Merit – Television | Won | [13] |

| Konex Award | 2007 | Personal | Platinum Konex Award | Won | [13] |

| Konex Award | 2017 | Personal | Diploma of Merit – Television | Won | [13] |

| Konex Award | 2017 | Personal | Platinum Konex Award | Won | [13] |

References

[edit]- ^ "Lanata renunció a Crítica de la Argentina para ir al canal de Pierri". 4 April 2009. Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ Agustín José Lanata, Historia de Boca, archived from the original on 9 May 2016, retrieved 11 July 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "La muerte de Jorge Lanata: año a año, los hitos más importantes de su carrera" [The death of Jorge Lanata: year by year, the most important milestones of his career] (in Spanish). La Nación. 30 December 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "Murió Jorge Lanata: 5 investigaciones que marcaron una era" [Jorge Lanata died: 5 investigations that marked an era] (in Spanish). La Nación. 30 December 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ a b c Daniel Gigena (30 December 2024). "La biblioteca de Jorge Lanata: de las crónicas y las novelas a las memorias del paladín del periodismo argentino" [Jorge Lanata's library: from chronicles and novels to the memoirs of the champion of Argentine journalism] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

- ^ a b c Pablo Mascareño (30 December 2024). "Jorge Lanata: de su llamativo matrimonio con Silvina Chediek al amor con Elba Marcovecchio que encendió un conflicto familiar" [Jorge Lanata: from his striking marriage with Silvina Chediek to the love with Elba Marcovecchio that sparked a family conflict] (in Spanish). La Nación. Archived from the original on 31 December 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ "¿Cuáles son los problemas de salud de Jorge Lanata?" [What are Jorge Lanata's health problems?] (in Spanish). La Nación. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ "Elba Marcovecchio rompió el silencio, habló de los últimos días de Jorge Lanata y de todo el conflicto familiar" [Elba Marcovecchio broke the silence, spoke about Jorge Lanata's last days and the entire family conflict] (in Spanish). La Nación. 15 January 2025. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ "De qué murió Jorge Lanata" [What Jorge Lanata died of] (in Spanish). La Nación. 1 January 2024. Archived from the original on 2 January 2025. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ Camila Súnico Ainchil, Lucila Marin, Paula Ikeda (1 January 2025). "La muerte de Jorge Lanata: entre aplausos y emoción, familiares y amigos lo despidieron en un cementerio privado" [The death of Jorge Lanata: amidst applause and emotion, family and friends said goodbye to him in a private cemetery] (in Spanish). La Nación. Archived from the original on 1 January 2025. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Murió Jorge Lanata: las reacciones del arco político, de Carrió a Macri" [Jorge Lanata died: the reactions of the political spectrum, from Carrió to Macri] (in Spanish). La Nación. 31 December 2024. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

- ^ "Milei habló por primera vez sobre la muerte de Lanata y contó cómo "salvó" a su perro Conan" [Milei spoke for the first time about Lanata's death and told how he "saved" his dog Conan] (in Spanish). La Nación. 8 January 2025. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Murió Jorge Lanata: todos los premios que ganó a lo largo de su carrera" [Jorge Lanata dies: all the awards he won throughout his career] (in Spanish). El día. 31 December 2024. Archived from the original on 1 January 2025. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

External links

[edit]- Jorge Lanata at IMDb

Media related to Jorge Lanata at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jorge Lanata at Wikimedia Commons

- 1960 births

- 2024 deaths

- Argentine journalists

- Argentine male journalists

- Argentine newspaper founders

- Argentine magazine founders

- Investigative journalists

- People from Mar del Plata

- Argentine male writers

- Argentine television personalities

- Argentine radio presenters

- Argentine film directors

- Golden Martín Fierro Award winners